Labor shortages have many companies turning to automation technology, but with mixed outcomes.

Logan Kugler

U.S employment statistics hit a new milestone last year, but not a positive one. In August 2021, almost 4.3 million workers quit their jobs, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. That’s the highest number since the department began tracking voluntary resignations. Their reasons for leaving their jobs vary—the numbers track people who quit for a different position, as well as those who quit without having another job lined up.

While the reasons for quitting vary, one thing is clear: Businesses are having a tough time getting employees to come back. A full 80% of companies surveyed by the Conference Board, a business research nonprofit, say they are now finding it difficult to hire qualified workers.

This is a win for worker wages. Additional Conference Board research predicts U.S. wage costs for companies will rise 3.9% in 2022, the highest jump since 2008. In the U.K., the National Institute of Economic and Social Research expects average weekly earnings growth to jump 5.9% in 2021, compared with 1.8% in 2020.

However, the growth in wages may not last.

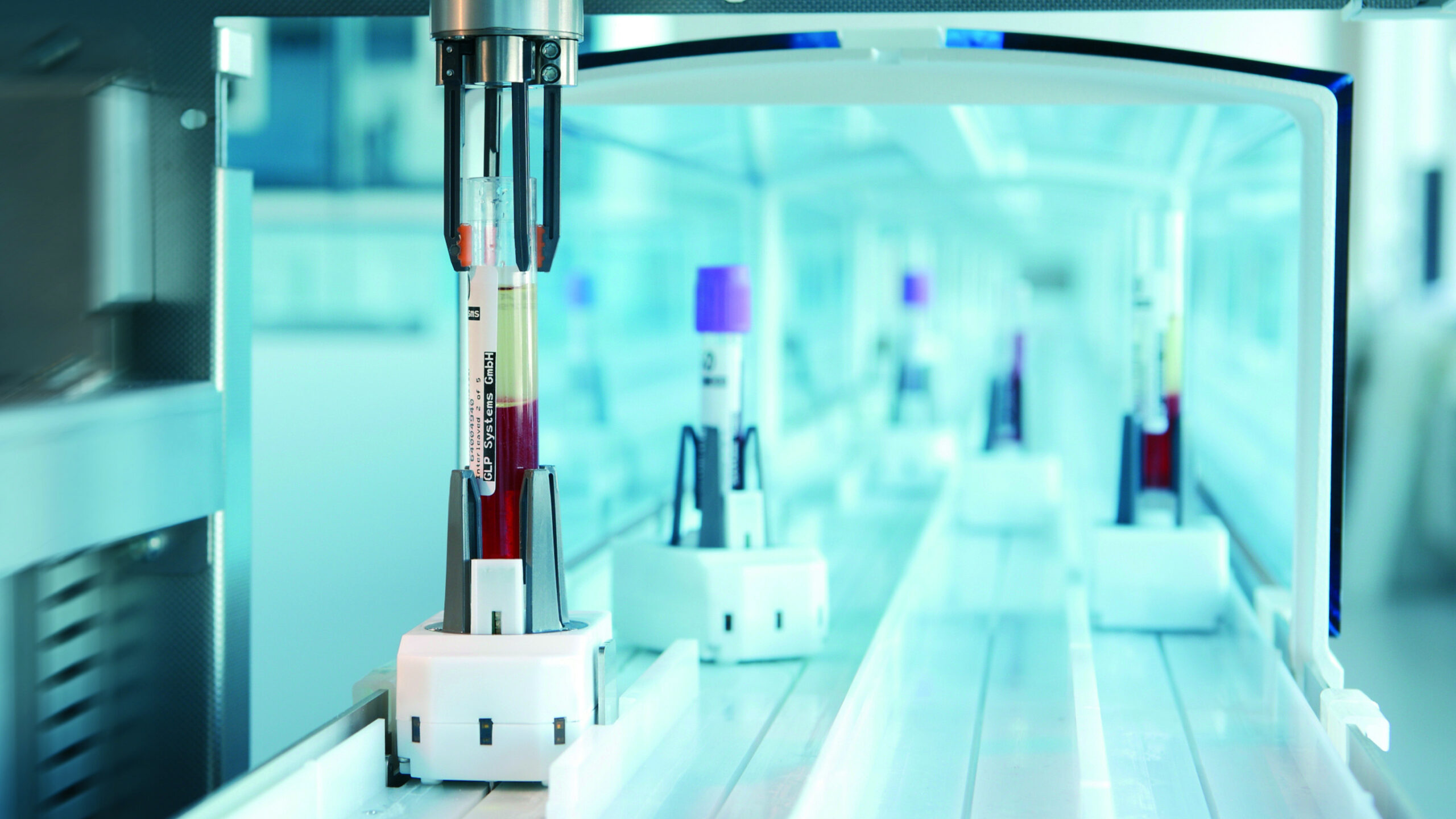

The labor shortage, combined with wages increasing to try to attract new employees and keep those they have, have led many businesses to accelerate plans to adopt automation technologies like robots and smarter software. Such adoption is happening across industries like manufacturing, the service industry, and administrative work. It is unclear if this automation will alleviate a permanent shortage of workers who no longer want this type of work—or if it will permanently eliminate jobs that may be in future demand.

The recent surge in demand for automation started out as a temporary necessity, says Gad Levanon, vice president of Labor Markets at the Conference Board and founder of the organization’s Labor Market Institute.

Many companies had to limit human interactions in order to comply with public health regulations during the pandemic. Using automation to take services online or rollout self-service options was the only way for some companies to keep doing business legally. However, as businesses reopen, many now see automation as a sensible permanent solution to the labor shortfall they now face.

“After massive layoffs during the early months of the pandemic, some have learned to operate with fewer workers by using more automation and other process improvements,” says the Conference Board’s Levanon says. ” 2021’s severe labor shortage and accelerating wages may incentivize other employers to do the same.”

Greater Demand for Fewer People

According to the Association for Advancing Automation (A3), which is described on its website as “the leading global automation trade association of the robotics, machine vision, motion control, and industrial AI industries,” orders for robots in North America rose 67% in the second quarter of 2021, compared to the same quarter of the previous year. In fact, it was one of the largest quarters for robot sales on record.

The customers for those industrial robots are in some surprising industries. More than half of Q2 2021 orders came from outside the automotive industry, says A3.

Automotive manufacturing is the leading consumer of industrial robot ics, so it is no surprise when the car industry buys robots. The greatest non-automotive industry increases in robotic acquisitions came from sectors like the metals industries, semiconductors and electronics, plastics and rubber, food and consumer goods, and the life sciences, pharmaceutical, and biomed sectors. These numbers reflect the demand for more automation in the manufacturing sector as a whole.

It is a trend Tom Kelly knows all too well. Kelly is the CEO of Automation Alley, a nonprofit that facilitates manufacturing private and public partnerships in Michigan. He says labor shortages have hit manufacturing hard, due to the pandemic and older workers exiting the workforce. During the pandemic, Automation Alley started connecting local manufacturers with automation technologies such as robotics. He and his team are finding manufacturers more willing than ever to test it out.

“We are seeing a demand for the lease of [automation] technologies,” Kelly says. That is because it permits companies to try out the automation equipment without first buying it outright, he says.

Kelly is not worried that automation will gut employment in the manufacturing sector. Not only does it increase productivity, but it can also empower workers to move up the value chain, he says. That allows them to do more valuable work with higher output, which can positively impact their wages.

“Automation reduces time spent on repetitive tasks, and most factory workers would welcome automation to free up their time to get upskilled to do more meaningful work, or work that involves creativity and strategy,” Kelly says. “This won’t replace people, but will increase flexibility for workers.”

However, automation doesn’t always empower workers in other sectors; in some sectors, automation is replacing humans entirely.

A range of companies in food service are experimenting with advanced automation that could reduce headcount permanently. As the industry hit hardest by the pandemic and the resulting labor shortage, food service players are desperate for automated solutions.

Fast food chain White Castle is rolling out a robot named Flippy built by Miso Robotics. Flippy can automatically cook different foods. The latest version of the robot can man an entire fry cooking station by itself, without human intervention.

KFC Korea is also going heavy on automation. The company recently partnered with Hyundai Robotics to automate the chicken-frying process. The work hinges on using collaborative robots within the kitchen to churn out consistent-quality chicken at speed.

Automation is not just eliminating human labor that makes food; it also is doing the work of food delivery labor. The food delivery market has tripled in size since 2017 to more than $150 billion, according to data from market research firm McKinsey, which found the market has doubled since the beginning of the pandemic. To handle that burgeoning demand amid a labor shortage, companies want to automate their delivery vehicles.

Pizza chain Domino’s has partnered with a company called Nuro to test self-driving pizza delivery robots. After placing an order, customers meet the small robotic vehicle at their doorstep, where they can enter a custom PIN into a door on the vehicle and retrieve their food.

Grubhub has started to experiment with automating food delivery, too. The company has partnered with Yandex NV to test self-driving delivery vehicles on college campuses. Other major fast food chains, including Chick-fil-A, have similar autonomous delivery initiatives in the works.

In fact, the pursuit of automation is so fervent in this industry that an entire new category of automation called food tech has arisen. Food tech describes the market for robotics, automation, and data-driven technology in the food industry, which includes both manufacturers of food products, and the logistics sites and apps that deliver them to consumers. Driven by the pandemic and the continuing labor shortage, this category is expected to explode to a $342-billion-per-year market by 2027, according to Emergen Research.

It is not just food service and food tech that are pursuing automation, either. Administrative workers are also under increased threat of replacement by automation, says Levanon. The need to increase contactless payments and transactions during the pandemic, as well as temporary or permanent office closings, has furthered automation in this space. At the same time, the need for in-person administrative or customer-facing staff was reduced or eliminated entirely.

“The accelerated digital transformation of both business and consumer activities now makes it easier to eliminate routine jobs,” says Levanon. “This resulted in many in-person customer service positions, such as health care receptionists, commercial banking tellers, and reservation ticket agents being eliminated in favor of online help and automation.”

The Automated Future

There is no doubt automation is replacing certain job functions, but will automation actually deprive human laborers of employment, or just fill jobs or job functions nobody wants? For clues, look to an industry that already has embraced automation to solve labor shortages: agriculture.

“In agriculture, harvesters were developed for field crops like wheat and soy many years ago,” says Diane Charlton, a professor who studies farm labor at Montana State University. “Firms are incentivized to automate because fewer workers are willing to work in agriculture.”

The pursuit of automation is so fervent in the food sector that an entire new category of automation called food tech has arisen. The agricultural labor market has long since had built-in friction that mirrors our current labor shortage. Even if farmers offer higher wages, there still may not be enough workers interested or available to fill positions. That’s because immigrant labor is the backbone of agricultural labor market, but the flow of this migrant labor each season is not fixed due to a range of political and economic factors. (Not to mention, the work can be back-breaking.)

Consequently, agriculture was forced to automate. Today, automated harvesters do some agricultural work, while other types of robots augment the efforts of human laborers. As a result, the number of workers needed in the field has decreased, says Charlton. However, more workers ended up needed in related agricultural industries, creating different types of jobs. These include jobs managing and maintaining robots, positions demanding more complex skills and commanding higher wages.

However, that future is not certain, notes Charlton. Many individual people and companies were ruined by automation in agriculture, such as small farms that could not afford to expand quickly enough to compete with major agricultural concerns deploying automation at scale. In addition, the skills required for a more automated world are different from those that were rewarded pre-automation. Workers who cannot adapt—or who try to return to jobs in automated industries—may find themselves out of luck.

“As with most major changes to the economy, there are winners and losers,” Charlton says.

Sumber: ACM Magazine